- Home

- Laura Burns

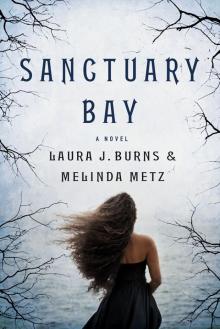

Sanctuary Bay

Sanctuary Bay Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Authors

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Laura J. Burns, click here.

For email updates on Melinda Metz, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

PROLOGUE

Daddy pressed his finger to his lips, shushing Sarah quiet as he slid the door to the tunnel back on. She wrapped her arms tightly around her knees and pressed her cheek against her arm, trying to pretend she was back in her own room. But it didn’t smell like her room. Even the spicy smell of Daddy’s cologne had faded now that the tunnel was closed. And grayness was all around her. She was almost four, and that was too old to be scared of the dark. But it wasn’t all dark. It was just gray dark.

She tried not to think of monsters crawling toward her. Daddy said there were no monsters. But monsters liked tunnels. They liked little girls.

Sometimes when she was scared she liked to sing the Maggie song. But that was against the rules. She had to be quiet. She had to be still. She had to wait until Daddy or Mommy opened the door and got her.

Thinking about the rules helped. She could almost hear Daddy saying them, as if he was hiding in the tunnel with her. Even though he was way too big. If something bad happens, wait until the room is safe. If you leave the tunnel, put the funny slitted door back on. Run fast. Find a lady with kids. Tell her your name is Sarah Merson. Merson. Merson. Merson. Merson. Ask for help.

Her nose started twitching, itching from the thick air. Making her want to sneeze. But she had to be quiet.

Then she heard Mommy screaming. Mommy never screamed. Were the monsters out there and not in the tunnel?

On hands and knees she started creeping toward the slits of light, heart pounding.

“Kt85L is our property,” a man said. “You had no right!”

Out there. Mommy on her knees facing the hotel room wall.

Someone’s legs. A hand reaching down. A silver bird stared at Sarah from a ring on the finger. Stared with a horrible little black eye. The finger pulled the trigger of a gun.

A bang. Her ears filling with bees. Mommy collapsing on the floor. Red spilling out.

Sarah shoved her fingers into her mouth. Quiet. The rule was be quiet.

Shouting. Daddy’s legs running by, out of the room. The bird man chasing. The door banging closed.

Something bad happening.

The room was safe. The bird man was gone. So she had to get out. Mommy was on the floor. Daddy was gone.

She shoved the door and it fell out onto the floor. Near Mommy. Near the red. But the rule was to put the funny door back on. She picked it up and shoved it over the tunnel like Daddy had shown her.

Sarah didn’t want to look at Mommy. She looked out the window instead. The window was always open and there was never a screen. Daddy’s voice came from the hallway, yelling. Screaming.

Another bang.

Sarah pressing her hands over her eyes. Not looking. Not looking. Something bad happening.

Daddy was quiet now. Something bad. She had to run fast.

Sarah climbed on the chair under the window. The chair always went under the window. She stuck her legs through the window and jumped down. Now run fast.

She ran fast, looking for a lady with a stroller or a kid her age. A mommy would help her. She would say she was Sarah Merson.

Sarah Merson, and something bad happened.

1

“First time on the water,” the captain said.

It wasn’t a question, but Sarah nodded as she tightly gripped the rail, the chipped paint rough under her palms. The rolling motion of the ferry made her stomach churn. “First time anywhere,” she mumbled. Ever since she’d left her latest foster home behind in Toledo, that’s all she’d had. First plane ride, first time out of Ohio since her parents died, first Greyhound ride, first boat.

An entire day of firsts thanks to what was probably a clerical error made by Sanctuary Bay Academy. The elite prep school had handed her a scholarship, even though she hadn’t applied or been recommended, even though the records from her countless schools made it sound like community college was her best hope—if she even got that lucky.

The chilly Maine wind blasted across her face, stinging her eyes and turning her kinky hair to a tangled mess. “Do you ever get used to how big it is?” she asked. “The ocean?”

The captain laughed, his red face crinkling. “Try being out in the middle, where you can’t see the shore.” He swung himself onto the steep staircase and headed down to the enclosed bottom deck.

Now her only company was a big white dog tied up near a stubby, rusty metal … thing … with a thick rope coiled around the base. Her perfect memory would tell her what it was if she’d ever come across it in a book or heard someone talk about it before, but that hadn’t happened. The dog’s tongue hung out of his mouth happily as they bounced roughly over the water, the ferry leaving thick trails of white spray as it plowed toward Sanctuary Bay Academy. Clearly the dog had more travel experience than her.

She turned around, facing the shore to get a break from the out-to-infinity view. But now all she saw was the rest of the world slowly getting farther away. If her social worker was right, if the scholarship was the real deal, she wouldn’t see that world again for almost two years. The academy had a strict policy of isolation.

Not isolation. Total immersion. Nothing but school.

But it still meant no contact with the outside world until she graduated.

“Which doesn’t matter,” she told the dog. “Seeing as I have no friends or family to miss.”

Her last foster family, the Yoders, they’d been okay. Sure, they were extremely white. Big and blond and rosy cheeked and just … white. Sarah was sure when they looked at her they saw a black girl with kinky-curly dark hair and a wide nose. But it had been no different when she’d had black foster families. It wasn’t as if they saw a white girl when they took in her green eyes and latte-hued skin. But they didn’t see themselves, either. They didn’t see black. If she’d been one thing or the other, instead of both, would she have found a place—a family—that she really fit with?

She’d never fit at the Yoders. Besides the whiteness, they were just too normal. Three-square-meals-a-day-bowl-a-few-frames-this-Saturday normal. Creepy normal. But she’d liked it there. No one tried to slide into bed with her. There’d been no hitting or screaming—Mr. and Mrs. Yoder actually seemed to like each other. Decent food. Some new clothes. From Target and Walmart, but new, and hers. Mrs. Yoder had even cried when she hugged Sarah good-bye this morning.

“Maybe she’ll miss me,” Sarah said quietly. She faced the ocean again, and the dog gave her a wag.

“I’m not petting you,” she told it. She didn’t have much experience with dogs. It was one of her gaps, or at least that’s how she thought of them. She’d lived in so many different homes, with so many different people. She should have experienced more than the average sixteen-year-old, but she had a bunch of gaps. Friends—you couldn’t make real friends when you switched schools that often. The ocean—the Maumee River in Toledo didn’t come close. Dogs�

��none, except the one the Weltons kept chained to the front door, and that one wasn’t exactly a tail wagger. Parties—she’d never even been invited to one.

Never had a pony or a Lexus with a bow on top for my sweet sixteen, either, she thought, mocking herself. “I just wish this part was over, the not knowing,” she said aloud to the dog. She could deal with anything as long as she knew what was going on. It was the not knowing that had her stomach roiling, no matter how many times she tried to tell herself it was only seasickness.

The dog stood up, so it could wag its whole butt and not just its tail. It moved closer, until its leash pulled taut, choking it. “Stupid mutt,” she muttered, but it kept on wagging. Okay, fine. Today was New Thing Day, so what the hell. Sarah slowly stretched her fingers out just far enough to brush its head. A second later, her hand was thoroughly slimed.

She smiled, wiping the drool on her jeans. “Thanks for not eating my hand,” she told the dog. “I’m weird enough already. I don’t need to be known as Stumpy the Scholarship Girl.”

Would that be a thing? Would there be a big divide between scholarship kids and everybody else? At her public schools the rich kids had always stayed away from people like her—well, at least at the schools she’d gone to that even had rich kids. But Sanctuary Bay was way beyond that. Her social worker had said students got their pick of colleges after graduation, that the best families in the country sent their kids here. That meant not just rich kids, but outrageously rich kids. Kennedys and Romneys and people like that. Sarah had tried to find information about the school online, a picture or something.

But she hadn’t found anything. Maybe since Sanctuary Bay had such an amazing reputation they didn’t need to be online. No need to advertise. If they wanted you, they’d let you know.

And they wanted her.

Or they wanted Sarah Merson at least. There had to be another one out there somewhere. A Sarah Merson with fantastic grades and a normal brain and parents who were still alive to help her get into a school like this. A girl who’d never been accused of being on drugs or cheating. A girl no one had ever considered might be “emotionally unstable,” to quote Sarah’s seventh-grade teacher. That was the girl who was supposed to be on this ferry.

“Maybe they’ll never figure out they screwed up. Sucks for the other Sarah, but I probably need it more than her, right?” she asked the dog.

The boat veered to the left, bringing what looked like a row of the world’s biggest floor fans into view. They had three blades each and were mounted on enormously tall yellow pillars—she guessed they were about four hundred feet tall—and each pillar was attached to a floating platform.

As they continued steadily toward the platforms, Sarah realized that two people were standing on one of them, inside a small white metal railing wrapped around the bottom of the platform’s pillar. One of them pointed at her, and then they both started to wave. Sarah turned around to make sure no one had joined her on the upper deck. Empty.

“You know these people?” The dog whined in response. They were probably just waving to wave.

The boat kept speeding toward the platform. It must be farther away than it looks, Sarah thought. Because it looked like they were going to run right into it if they kept going for much longer. She heard footsteps clambering up the metal stairs. “You, let’s go,” the captain called to her.

Sarah grabbed her suitcase and her backpack. “Wish me luck,” she murmured to the dog before she started toward the stairs. The dog wagged, as if to say it was all good. But it wagged at everything. How could this be my stop? she wondered. She’d never been on a ferry though. Maybe he was just getting her ready for a stop that was coming up in twenty minutes.

“Anything fragile in your gear?” the captain asked.

“Uh, no. Mostly just clothes,” Sarah told him. Foster kids traveled light. The boat veered, pulling up alongside the platform. Now she could see the two people standing by the pillar were around her age, a boy and girl. They were still waving.

“Hi, Sarah! We’re your welcoming committee,” the boy—on the short side, muscular, cute, close-cropped dark brown hair, Hispanic—called to her.

“So, welcome!” the girl—preppy-pretty, straight red hair, white—added.

She sighed. Sarah always got frustrated when people tried to put her in a black or white box, like it had to be an either/or thing. But more frustratingly, she found herself automatically doing it too. She saw someone and checked off boxes. Size. Age. Race. Attractiveness. Economic status. But race was always there because it was the one box that she never knew quite what to check for herself.

The captain took her suitcase and heaved it over the rail. It landed on the floating platform with a thump. Sarah blinked in surprise. “Nothing breakable, you said.”

Sarah managed to nod. She was starting to get blender-brain. It was only yesterday that her social worker had told her about Sanctuary Bay, while Mrs. Yoder buzzed around excitedly. And since then it had been pow, pow, pow—new stuff thrown at her every second. Now she was getting dropped off in the middle of the ocean onto a platform the size of a basketball court.

Oh, but wait. There was a boat tethered nearby on the other side. She’d been so focused on the people and the high fan—a wind turbine, her brain had finally provided when she’d realized she had arrived at a floating wind farm—that she hadn’t noticed it. It looked more like a spacecraft than a boat, a spacecraft for James Bond. Low to the water with sleek metal lines, stretching out in two long points in front of a glassed-in … she wanted to call it a cockpit, but she was sure there was a better word. One word that definitely applied to the whole thing was magnificent. Just magnificent.

“You want to wear the backpack down, or should I toss it too?” the captain asked after a long pause. Sarah looked over at him and saw that his eyes were wide, locked on the boat beside the platform. So she wasn’t the only one who thought it looked like something that wouldn’t be invented for decades. The guy who made his living on the ocean did too.

“Toss it,” Sarah told him after realizing she was going to have to awkwardly climb down a metal ladder running down the side of the ferry.

“Sarah Merson, come on down,” the boy cried in a cheesy TV-show announcer voice, like she was a contestant on The Price Is Right. He gave her a cocky grin. He knew exactly how cheesy he was being and that he was hot enough to pull it off. More than hot enough.

Did rich people even watch The Price Is Right? The boy waiting for her at the bottom of the ladder definitely seemed like a rich boy, knowledge of PIR withstanding. Except it looked like his nose had been broken at least once, and it hadn’t been returned to perfection with plastic surgery. The girl looked rich too. They both just had a well-groomed glow that she’d never seen outside of Us Weekly. Not that Sarah was smelly with chipped nail polish or anything. But there was a difference.

Don’t stand here staring, she told herself. You’ve done this all before. Not the boat part, but she’d been the new girl too many times to count. And she still hated it. Don’tfalldon’tfalldon’tfall, she thought as she stepped onto the ladder, her sweaty palms sliding across the metal railing. She narrowed her focus to the steps until she reached the gently bobbing platform.

“Nate Cruz,” the boy said, holding out his hand. She shook it, praying her palms were no longer sweaty. “Junior class president,” he added. His eyes were a golden brown, like caramels, his skin just a few shades darker, and the way he looked at her made her feel like she was the only person not just on the platform, but in the entire world. She was relieved when the girl stepped up beside them. Nate’s gaze was so intense she felt like she needed a reason to look away.

“I’m Maya,” the girl announced. “I don’t feel the need to give my title every three or four seconds.” She smiled, shaking hands with Sarah too. It was kind of like they were all at a business meeting, or what Sarah imagined a business meeting would be like, anyway.

“She doesn’t feel the need to an

nounce her title because she’s class secretary, and it’s not worth mentioning.” Nate shot Maya what Sarah was already starting to think of as The Grin, then wrapped his arm around her shoulders. Maya tried to pull away, but he gave her smacking kisses on the cheek as he pulled her tighter against him.

So that’s how it is, Sarah thought. Good to know. She liked to figure out as much as she could about the people in a new place as soon as possible. It made her feel more in control. Nate and Maya a couple. Noted.

Have I said anything? She felt a spurt of embarrassment. Had she just been standing there gawping at the pretty, shiny boat and the pretty, shiny rich kids? Say something. Anything. Anythinganything. “I thought the ferry would take me all the way to the school,” she mumbled.

“Nope, the school’s boat brings students the rest of the way. No need for a regular ferry to Sanctuary Bay,” Maya answered. “Once you arrive, you’re there ’til grad.”

“But don’t worry about not being able to leave,” Nate told Sarah. “We make our own entertainment.”

“We do.” Maya gave her words a spin, making it clear she was talking about epic sex. “The only thing I really miss is shopping,” she added. “We can get packages every three months, but that just means we get what people think we want. My mom tries, but she’s basically hopeless, or else she thinks I’m still in fifth grade. Some of the stuff I get? I’m like—‘Seriously, Mom?’ Doesn’t matter though. There are always people who want to trade.”

Sarah remained quiet. She didn’t think her first thought, That’s what we call a first-world problem, bitch, was quite the right way to go about making friends. Instead she turned to Nate. “And you?” Sarah asked. “Does Mommy still think you’re a little boy?” The words came out with an edge she hadn’t intended.

“I’m past the age of needing a mommy,” Nate answered, his own tone a little sharp. “Let’s get to Sanctuary Bay so you can see the place for yourself,” he quickly added, the warmth back in his voice. He gave a light rap on the smoked-glass roof of the cockpit. A second later the back slid up, smoothly and soundlessly, revealing six matte-black leather chairs, ones that could easily sit at some swanky bar without looking out of place.

Sanctuary Bay

Sanctuary Bay